By Kent H. Benjamin

From Pop Culture Press, Issue 56, Spring 2003

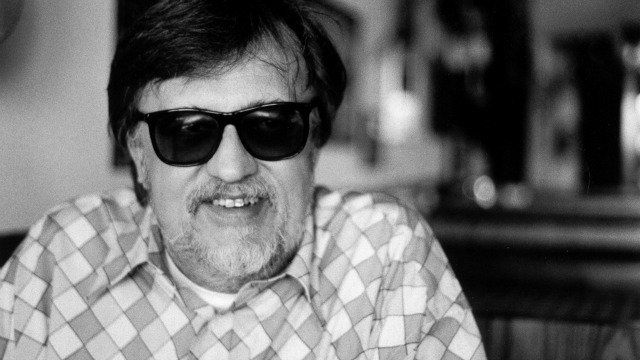

While one would hope the legendary Memphis musician, producer, and incorrigible raconteur Jim Dickinson needs no introduction to most of our readers, the truth is he isn’t exactly a household name, but rather one of the great cult figures in the history of southern rock. Whether you know the name or not, you have heard his music. Many times, in fact.

Jim Dickinson was playing what was then called “race music” well before most white boys in the Mississippi Delta. As a young adult, he sang lead vocals on the last single released on Sun Records, “Cadillac Man,” by The Jesters. He was a founding member of The Dixie Flyers, who went on to be the house band at Muscle Shoals Studios in Alabama in the early ‘70s, backing artists including Aretha Franklin. He played piano on the Rolling Stones’ FM staple “Wild Horses” and appeared in the film Gimme Shelter. He went on to be Ry Cooder’s musical sidekick on many film soundtracks including Paris, Texas, The Long Riders, and Crossroads (the Robert Johnson film), and his song “Across the Borderline” was cut by Willie Nelson and performed by Bob Dylan at Farm Aid. (“that paved my driveway,” he joked). He formed the last great Memphis all-star supergroup, Mud Boy and the Neutrons, and provoked near-riots and incidents for years in Memphis. He produced Big Star Third/Sister Lovers for Alex Chilton and Big Star, which became one of the most influential albums of the ‘70s — heck, of any era.

He later produced The Replacements, The Gunbunnies, Jason & the Scorchers, Green on Red, The Radiators, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Mudhoney, The Texas Tornados, Steven Forbert, G. Love & Special Sauce, Dash Riprock, and many others. As a session musician, he’s worked with Dylan, Los Lobos, Primal Scream, The Flamin’ Groovies, Delaney and Bonnie, Rocket from the Crypt, and many, many more.

Dickinson’s first solo album, released in 1972 on Atlantic (who employed the Dixie Flyers), was entitled Dixie Fried, and has become a cult classic, one of the most endearingly off-center records in many fans’ collections. It’s been reissued (on Sepia Tone) and his first new solo album in 30 years, Free Beer Tomorrow, (Artemis Records) was released in the fall of 2002, and gleefully follows in the footsteps of Dixie Fried. Dickinson is accompanied by his boys, Luther and Cody, nowadays known as two-thirds of the Mississippi All-Stars, both who’ve become recognized as musicians and producers in their own right. We chatted with Dickinson about his album on the weekend after Thanksgiving, 2002. Here are the parts we can print, in James Luther Dickinson’s own words, mainly dealing with some of his extraordinarily obscure and eclectic choices of material to cover, and how Free Beer Tomorrow came to be.

Free Beer Tomorrow

The cover photograph is of a sign in a cafe in Memphis called The Green Beetle. It’s a childhood memory. I assumed I knew where it was, but I didn’t, so I had to dig up a picture of the thing. It’s been gone for many years. I’m really pleased with what I got, but it’s not exactly what I had planned. I’ve had that cover planned for 30 years. That’s where the sign was that said ‘Free Beer Tomorrow.’ My father took me there as a kid, and some things you never forget.

“Ballad of Billy & Oscar” from Free Beer Tomorrow

Stanley Booth played that for me years ago. Like several of the other songs on the record, I basically considered it unrecordable until I found the handle on it. On Dave Hickey’s original version, which I gather had never been released (it must have been just some kind of demo), he sings it like an Elizabethan ballad with a 12-string and a cello and an oboe, and it’s very different. I wanted to do some kind of semi-resuscitation on the record, and I figured I could do “Billy and Oscar” that way. I formulate a record, especially after it’s done and I am sequencing it, based on a Tex Ritter album I had when I was a kid (when I say album, it was a series of 78s). It was called Cowboy Tex Ritter Sings Children’s Songs and Stories. It had “Billy the Kid” and “Wreck of the Old 97” and it had this recitation called “The Phantom White Stallion of Skull Valley.” If I live to make a third record, that’ll be on it.

Before I considered recording “Oscar and Billy,” I just listened to it. I’d listen to it about once every six months just to make myself feel better about being a human being. I kinda think it does that. It strikes a familiar déjà vu note in your mind that’s almost like “oh yeah, I’ve heard that story somewhere.” I don’t know, it’s just about heroes. And heroes are not all Spider Man. Billy and Oscar are both heroic.

Blaze Foley’s “If I Could Fly”

I saw Blaze Foley only once, at the Austin Music Awards at SXSW one year. He was all covered in duct tape. I didn’t know who he was when I saw him. I didn’t really get into him until after he was dead, when I was working with [Austin artist] Calvin Russell [as a producer]. Calvin had a lot of tapes of Blaze live. I ended up with a nice collection of his stuff. Truly a remarkable artist. “If I Could Only Fly” is my favorite song that I’ve ever heard. I played it last night at a gig in Memphis with my boys. It says something to me.

There was one particular guy who hung around the sessions. I never did know his name, and he had a lot of Blaze’s tapes. Calvin had a lot of criminal-type friends, and you didn’t want to ask too many questions. For every miracle like Bob Dylan, there are probably 5,000 horror stories like Eddie Hinton or Blaze Foley. These songs just haunt me. It’s on a scale that the best voices in the world just couldn’t record — where the better you get, the harder it is. Blaze is just an incomparable talent when you hear all of his songs. Of course, he’s best known for his comedy songs. But as deep as the comedy goes, so goes the tragedy. The serious songs are just unbelievable. The reason I recorded it, although I would have recorded it anyway, at the time I started this record, all of Blaze Foley’s work was tied up contractually. And “If I Could Only Fly” had been recorded by Willie and Merle years ago, so it had been cleared as a published song. But not taking away from Merle Haggard’s version, he doesn’t have the chromatic guitar part in there, which I found on an Austin tape. That chromatic walk up on the guitar right before the chorus sounds just like Willie, and that’s just a signature of the song for me. That’s what sets it all up. But, you know, a lot of Blaze’s songs, at the heart of them he was trying to pick up a girl in a bar so that he’d have a place to stay that night, you know? And that element is in this song. In the first verse, I think he’s clearly addressing his mental condition. I think he’s singing about being crazy, and that really appeals to me.

Was it Deliberate That “If I Could Only Fly” Had a “Wild Horses” Feel to It?

It very definitely was. I’d like to say that this record was more spontaneous than it is, but it was all too thought out. So at this point, 32 years after I played on “Wild Horses” (Jim was 61 at the time of this interview in 2002), I made this record to an extent for the fans in the stands. They may not be legion, but they’re there. And they have expectations. So I referenced Dixie Fried, I tried to reference my film work with Ry Cooder, I tried to reference Big Star Third, which is harder to hear because it’s all technical stuff, like depth of echo and that kind of thing. But I figured that I had fans of these other projects, so I did try to reference them.

Eddie Hinton and “Well of Love”

Eddie Hinton… I wish I knew what happened to Eddie. Roger Hawkins said he just couldn’t deal with the rejection, and he never got anything but rejection. His health just failed him and he died. He died on the commode like Elvis, which is where the similarity ends lifewise. He was at his mama’s house, completely broke and destitute. He played on my Toots in Memphis record (Dickinson produced a brilliant album for Toots Hibbert of the reggae greats The Maytals, some years back). He didn’t even own a guitar. Way back when I was feeling really frustrated, I would think about Eddie, or Teenie Hodges, and think about how they must feel. I never saw more talent in any one person than Eddie Hinton had. And again, that’s the same story, that the better you are, the harder it is. Whatever it is that makes crazy white boys want to sing black music, Eddie had more of it than the rest of us. I don’t know, maybe he had too much. And there’s another song, “Well of Love,” that I had considered unrecordable until we got that arrangement. I was trying to record another Eddie Hinton song. “Every Natural Thing,” and had no luck with it and Luther suggested “Why don’t you try ‘Well of Love’?” I had a handwritten set of the lyrics that Eddie had written himself, so I figured it was worth a shot. I think we got close. It doesn’t have the same animal desperation of Eddie’s version.

“Bound to Lose” – Originally by the Holy Modal Rounders

I’ve wanted to record that Holy Modal Rounders Song since before Dixie Fried. It’s a song I couldn’t get the Dixie Flyers to play [on that album they were the backing band]. I saw the Rounders in ‘63 in Cambridge, along with Kweskin’s Jug Band, and it was real important to me to see these Yankees playing my music, so I figured I better get busy. [According to Nick Tosches’s liner notes, “Bound to Lose” was written by Peter Stampfel of the Rounders, who released it in 1963, but Stampfel told Dickinson that Bob Dylan had written the song. [When Dickinson worked with Dylan on Time Out of Mind, he had the opportunity to ask Dylan about the song, and Dylan said: “Peter Stampfel wrote it. Is he still crazy?”]. That’s exactly what Dylan said — “Is he still crazy? I think from what Tosches said that Dylan did write the song. That he’s just passing it on.

Asshole

“Asshole” was written by Mark Unobsky; I went to high school with him. Of all the crazy white boys trying to play acoustic blues, he was the best of them. He makes Cooder sound like he’s playing the ukulele. He’s dead now. He lived in San Francisco for years. He wrote some songs, but he couldn’t publish ‘em ‘cause he was on disability. He basically had a lifetime income of selling guns and dope to the Grateful Dead. I first heard that song in the ‘70s, and I thought “God, what a wonderful song, but nobody’ll ever hear it.” And they are literally playing it on the radio now. That’s how much the world has changed. They’ve played it in Seattle, in Minneapolis, and they played it in Memphis last Sunday. It’s a love song about a woman. “…We’re in agreement on my soul…” [rhyming it with asshole] is what gets me. This guy was a weapons expert. Back in the ‘50s when everybody had a switchblade, he had a switchblade with four buttons and four blades. Shit jumped out of it everywhere. He was a remarkable human being, and an amazing guitar player. I don’t know whether you’ve ever heard my skinflick music for Great Big Fish, which was released on soundtrack in France, but he’s playing guitar on it, with the Bar-Kays. He was an amazing musician, and [was] almost completely unrecorded. He was the manager of The Charlatans in San Francisco in the ‘60s [the brilliant cult band with Dan Hicks and Mike Wilhelm], had the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Colorado [which was where the San Francisco scene was born]. The Charlatans were his house band, and he also supposedly was the first person outside of Texas to employ Janis Joplin. He had the first psychedelic light show and nightclub. “Asshole” is by far his best composition. With the arrangement of that song, I was trying to reference various things from my past. There was a guy in the original Today Show who played live with his band, called Art Van Damme and the Art Van Damme Quintet. They had vibes and accordion together, and that’s what I was referencing there, and showcasing that fiddle player, a local guy who I think is a fabulous soloist. And of course that’s Luther playing slide. He’s playing a guitar that Unobsky, the author of the song, left him in his will. Unobsky is basically behind the formation of the North Mississippi All-Stars. He talked to Luther about the idea of playing the Delta Blues with a power trio. That’s where Luther got it. He was a very private man who didn’t have many friends. Not only do I treasure his friendship, but he was a big help to Luther, when he didn’t have to be.

What’s Left to Accomplish?

I was thinking about what you said the last time we talked, and if there’s one thing I’d like to accomplish in my career, it’s this: I’d like to use my Baylor Film School training [Dickinson went to Baylor University in Waco, Texas, birthplace of Big Red, Dr. Pepper, the Branch Davidians, and the spiritual home of the Southern Baptists] and direct the film version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera starring Ozzy Osbourne in the title role. Can’t you just see that [laughing]!?

James Luther Dickinson was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1941 and raised in Chicago and Memphis. He left this mortal coil August, 15, 2009.

Leave a Reply